Program Overview

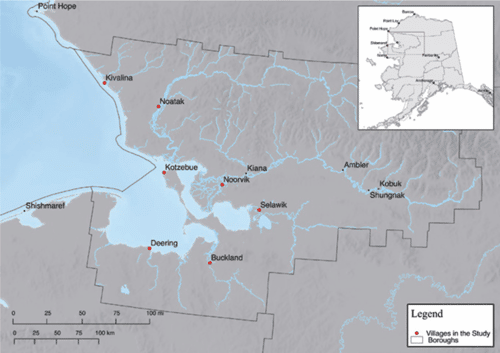

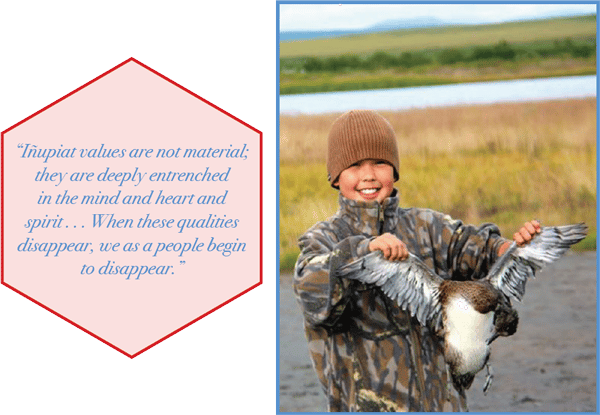

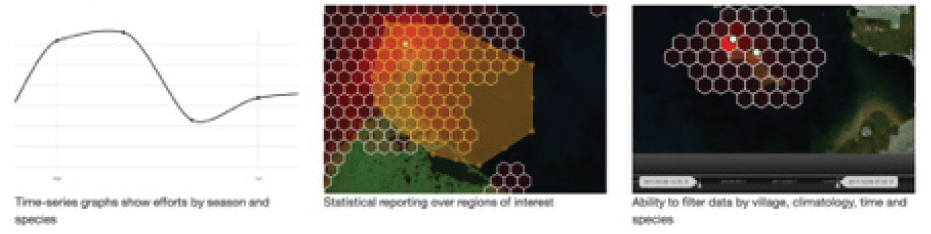

The Northwest Arctic Borough Subsistence Mapping Project documents local traditional knowledge and scientific information depicting subsistence use (where people hunt, fish, and gather by season) and important ecological areas (where animals feed, breed, raise young, and migrate by season) surrounding the communities of Kivalina, Noatak, Selawik, Noorvik, Deering, Buckland, and Kotzebue. The purpose of the project was to produce updated and scientifically defensible maps showing subsistence use and important ecological areas surrounding the Borough’s coastal communities for use in land use planning and commenting on federal plans, including but not limited to, offshore oil exploration and oil spill response.

AIKUULAPIAQ to the participating communities

- Kivalina

- Noatak

- Kotzebue

- Deering

- Buckland

- Noorvik

- Kiana

- Selawik